The rapid democratization of artificial intelligence has unleashed a formidable new weapon for cybercriminals, with hyper-realistic deepfake technology now capable of flawlessly impersonating senior executives to orchestrate massive financial fraud. This sophisticated evolution of social engineering is no longer a theoretical threat but a clear and present danger, creating unprecedented challenges for the cyber insurance industry. As attackers move from faking what employees read to convincingly spoofing what they see and hear, the traditional frameworks of insurance coverage are being stress-tested to their limits. The rise of this multi-sensory deception is forcing a fundamental re-evaluation of how policies are structured, how claims are adjudicated, and how businesses must overhaul their internal controls for a world where seeing and hearing can no longer be believing. The ensuing confusion over liability and coverage is exposing dangerous blind spots in corporate risk management and pushing insurers to a critical inflection point.

The New Face of Deception

Deepfakes represent a quantum leap in the art of digital impersonation, moving far beyond the text-based phishing emails that have long plagued corporate security. Criminals now possess the ability to create highly persuasive audio and video fabrications of trusted figures, turning the very tools of modern communication into vectors for attack. This technological shift allows them to bypass technical security controls by exploiting the most vulnerable element in any organization: the human tendency to trust. By staging a fabricated video call or leaving a manipulated voicemail, an attacker can transform a simple fraudulent request into a compelling, multi-sensory command that legacy security protocols and human intuition were never designed to detect. The realism is such that even trained professionals can be deceived, as was starkly demonstrated in a recent case where a finance employee in Hong Kong transferred over $25 million after participating in a video conference with what he believed to be his company’s senior officers, all of whom were AI-generated deepfakes.

This escalation from simple deception to sophisticated impersonation marks a pivotal moment in the history of cybercrime, with funds transfer fraud emerging as the primary and most devastating application. The effectiveness of these attacks lies in their ability to manipulate core psychological triggers, such as urgency, authority, and familiarity. An employee is far more likely to comply with a large, unusual payment request when it seemingly comes directly from their CEO during a live video meeting than from a text-only email. This method has proven to be incredibly effective, leading to staggering financial losses that can cripple an organization in a matter of minutes. The incident in Hong Kong serves as a chilling proof-of-concept, confirming that deepfake-driven fraud is not a distant, future risk but a present-day reality capable of inflicting catastrophic damage. The incident underscores the urgent need for a new paradigm in security awareness, one that teaches employees to question the authenticity of digital interactions, regardless of how convincing they may appear.

A Crisis of Coverage and Clarity

The emergence of deepfake-enabled fraud has plunged the insurance industry into a state of significant uncertainty, creating a coverage dilemma often described as a “pass-the-parcel” problem. These sophisticated attacks sit uncomfortably at the intersection of two traditionally distinct policy types, leading to friction and ambiguity during the claims process. The attack’s methodology, which leverages advanced AI technology and digital impersonation, gives it the technical “wrapping” of a cyber event. However, the ultimate outcome—a direct theft of funds through a fraudulent transfer—is the classic “present” of a crime loss. This duality creates a dangerous gray area, as insurers debate whether the loss should fall under a cyber policy, which covers technology-based risks, or a crime policy, which covers direct financial theft. This confusion not only delays claim payouts but can also leave businesses dangerously exposed if their coverage is not structured to address this specific hybrid threat.

This inherent ambiguity is further compounded by the structural limitations of existing insurance products, which were not designed with such multi-faceted attacks in mind. While a standard cyber policy may offer some limited coverage for social engineering, it is typically provided as a sublimit, often capped at a fraction of the overall policy limit. For example, a business might have a $5 million cyber policy, but the social engineering component could be restricted to just $250,000. This amount is grossly insufficient to cover the multi-million-dollar losses now being seen in successful deepfake attacks, leaving organizations with a false sense of security and a massive financial shortfall. The inadequacy of these sublimits highlights a critical failure of traditional policies to keep pace with the speed of technological change and the evolving tactics of cybercriminals. The industry is now grappling with how to close this gap, whether through new hybrid products or by demanding clearer delineations between cyber and crime policies.

Redefining Risk and Responsibility

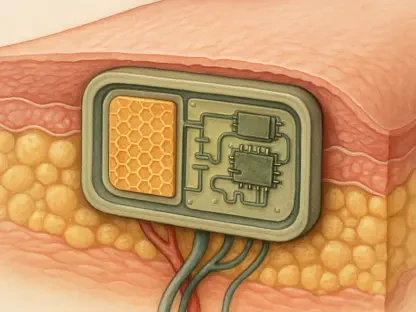

In response to this escalating threat, the insurance industry has begun to adopt a much more prescriptive and demanding approach during the underwriting process. Insurers are no longer satisfied with simple questionnaires; they now require tangible evidence of robust, multi-layered financial controls designed to thwart impersonation-based fraud. Underwriters are placing intense scrutiny on corporate governance, expecting firms to implement and enforce mandatory dual-approval processes for any changes to vendor payment details and for all significant fund transfers. The long-standing principle of segregation of duties, which prevents a single individual from controlling a financial transaction from start to finish, is also being heavily emphasized as a critical backstop against both external fraud and internal error. This shift signals that insurers are placing a greater share of the risk management burden back onto the policyholders themselves.

A pivotal change in insurer expectations is the fundamental reclassification of voice and video communications as inherently untrusted methods for transaction verification. The simple act of seeing a CFO on a video screen or hearing a CEO’s voice on the phone is no longer considered sufficient authorization for transferring large sums of money. Consequently, insurance proposal forms are evolving to include direct and specific questions about a company’s policies and employee training programs related to deepfakes and voice phishing, or “vishing.” This places the onus on businesses to prove they are actively adapting their internal culture and security protocols to this new reality. Unfortunately, a significant corporate training gap persists. While general phishing awareness education is now commonplace, very few organizations provide training on how to identify or respond to sophisticated audio-visual deception, leaving employees psychologically unprepared and highly vulnerable to manipulation.

A Mandate for Integrated Risk Management

The complex nature of deepfake threats required a more holistic and integrated approach to risk management, fundamentally changing the role of insurance brokers and risk advisors. The conversation had to move beyond the siloed discussion of a single policy and evolve into a comprehensive “portfolio” analysis that examined the intricate interplay between multiple coverages, including Cyber, Crime, and Directors & Officers (D&O). This necessitated that brokers proactively map out complex loss scenarios with their clients to identify potential gaps, overlaps, and points of conflict between different policies. It became clear that without a cohesive strategy, a company could find itself caught in a protracted dispute between its cyber and crime insurers following an attack, with each carrier arguing the other was responsible for the loss. To mitigate this, a practical strategy emerged: placing complementary policies, such as Cyber and Crime, with the same insurer to streamline the claims process and ensure a unified response when a rapid resolution was essential.

Ultimately, the fight against deepfake fraud reinforced the idea that technology alone could not be the sole line of defense. It demanded a renewed focus on strengthening human-centric security controls and fostering a corporate culture of healthy skepticism. Attackers frequently exploit human vulnerabilities, such as launching attacks late on a Friday afternoon when employees are fatigued and less likely to follow strict protocols. Therefore, the core of the insurance industry’s response centered on demanding tighter client controls, promoting clearer policy boundaries, and fostering a more cohesive advisory conversation around risk. The challenge underscored that for the insurance sector to remain relevant and effective against such a dynamic threat, it had to evolve from being a mere purveyor of siloed products to a true partner in building resilient, programme-wide risk solutions that acknowledged the sophisticated and ever-changing nature of cybercrime.