An evolving and comprehensive analysis of agricultural insurance reveals that the mental health of a farmer is no longer just a personal wellness issue but is now being recognized as one of the most critical and material risks to the entire farm operation. This shift in perspective is gaining significant traction, propelled by recent UK data showing that farmers’ mental wellbeing has fallen to its lowest point in four years. The downturn is compelling the insurance market to confront a risk it has historically struggled to quantify: the direct and tangible impact of stress, fatigue, and isolation on farm safety, operational integrity, and overall business resilience.

The conversation around agricultural mental health has traditionally been confined to a wellness framework. However, insurance brokers and industry experts now assert that its effects are manifesting as a measurable risk, directly influencing the frequency and severity of accidents. This growing concern impacts the volume of liability claims and the fundamental stability of farming enterprises, which often depend on a small number of individuals working in relentlessly high-pressure and high-risk environments.

The Overlooked Asset in a Field of Steel and Soil

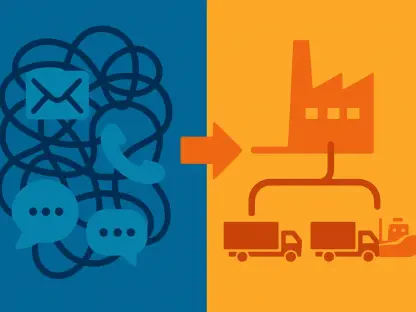

A central theme emerging from this re-evaluation is the systemic undervaluation of the “human element” in conventional farm insurance assessments. Traditionally, discussions during renewal reviews and new business quotes disproportionately center on cataloging and valuing physical assets like tractors, barns, and other equipment. While a standard industry practice, this asset-centric approach creates a significant blind spot by often undervaluing, or entirely ignoring, the mental and emotional state of the farmers themselves—the very individuals operating the machinery and managing the business.

This oversight represents a critical vulnerability. As industry experts point out, even the most meticulously managed farms remain exposed to the unpredictable nature of human error. The argument is that deteriorating, poor, or neglected mental health directly elevates risk factors on the farm. Consequently, a new understanding is taking hold: the policyholder is, in fact, the most valuable and most vulnerable asset, and protecting them is paramount to protecting the business.

Connecting Mental State to Mechanical Failure

The most sophisticated safety protocols and state-of-the-art machinery are ultimately susceptible to mistakes originating from an operator’s compromised mental state. This exposure is particularly acute in the agricultural sector, where individuals frequently work in isolation with large, powerful, and potentially dangerous equipment. From an actuarial or underwriting standpoint, a client who is not in a sound mental state while piloting expensive, heavy machinery alone in a field presents a clear and concerning risk profile.

This perspective directly challenges the traditional separation of physical safety from mental wellbeing. It posits that a mentally healthy workforce is as crucial as a physically safe one; one cannot effectively exist without the other. Together, they form the most robust defense against liability claims. The link is direct: a farmer struggling with stress or depression is more likely to be distracted, leading to operational failures that no amount of physical safeguarding can prevent.

From the Field a Clear Correlation Emerges

The connection between poor mental wellbeing and unsafe behavior is not merely theoretical; it is substantiated by compelling evidence from on-the-ground research. The Farm Safety Foundation, known as Yellow Wellies, has highlighted a direct correlation observed over years of study between farmers’ diminished mental wellbeing and a corresponding increase in unsafe working habits. Farmers experiencing lower levels of mental health exhibit concerning attitudes toward workplace safety, which translate into tangible and dangerous failures in day-to-day operations.

Specifically, the research indicates that these individuals are significantly less likely to conduct proper risk assessments and are more prone to admitting they cut corners to save time or effort. Furthermore, they frequently neglect to use essential personal protective equipment (PPE) and may even abdicate their personal responsibility for maintaining a safe work environment. These behaviors are not isolated incidents but patterns directly linked to the operator’s mental state.

The High Cost of a Momentary Lapse

The consequences of such behaviors are profoundly severe within an industry that already holds one of the most troubling safety records in the UK. Accidents on farms are rarely minor; they are often catastrophic events that result in life-changing injuries or fatalities. Experts underscore the gravity of the situation by explaining how even momentary lapses in concentration can lead to irreversible outcomes.

A farmer who is not in the right headspace—distracted by financial stress, anxiety, or depression—while operating a tractor or managing livestock can make a fatal error in a split second. This “momentary lapse of concentration” has the potential to permanently and tragically alter their life, the lives of their family members, and the future of their entire business, demonstrating the immense liability tied to this invisible risk.

Reframing the Conversation from Assets to People

For the insurance industry, this presents a formidable challenge, as the risk associated with mental health does not fit neatly into traditional assessment frameworks. Mental health is described as one of the least visible yet most consequential risk factors, leading to secondary effects like distraction and forgetfulness, which have costly implications. While some support mechanisms, such as confidential helplines, exist within certain policies, they are frequently overlooked because the focus remains on machinery.

A fundamental shift in these conversations is now being advocated. This change does not require turning insurance consultations into therapy sessions but simply involves asking different, more holistic questions. Brokers are being encouraged to pivot the discussion with a simple yet powerful framing: “We’ve just spent hours talking about your assets; can we have five minutes to talk about how we’re protecting you?”

This proactive approach reframed the policyholder as the most valuable asset of the business. As economic and environmental pressures on farming businesses intensified, brokers and insurers had been compelled to confront a reality that traditional risk models failed to accommodate. The growing chasm between operational reality and the insurance industry’s conventional framework had become impossible to ignore, solidifying the understanding that on a farm, human resilience was inextricably linked to risk exposure.